I have always known the importance of tradition through my family. I spent my childhood in East Germany and my summer and winter holidays were spent in my parents’ hometown, the Delta. My siblings and I developed in two worlds, one on top of the other—in an order that resembles the strata of earth with the lower world being foundational. The Yazoo-Mississippi Delta was (and is) that foundation.

The region (or space) provided answers to my parents’ names, speech, foodways, music and politics. All the answers were knowable in the small village hidden by trees, stretched over red mud and filled with generation of my folks and watermelon. One thing—maybe the most important thing—I learned from my folks, and the ground on which they stood, was to always speak to the elders that came and left the room. One learns early the seriousness of speaking to elders whom are moving in and out and through.

I am a young adult now, moving beyond the village that civilized me such, and those lessons remain. In 1984, 10 years before my sojourn back to my mother’s land, Toni Morrison published “Rootedness: The Ancestor as Foundation.” The essay addresses a series of issues with one at the center: criticisms of black novels. African-American novels’ ability to be “both print and oral literature” and “the presence of an ancestor” are of interest to this essay. The Nobel Laureate surmises that novels, like music or other black cultural products, are identifiable in their interaction with elders of the community, and sermonic tradition that brings that interaction forward.

In the eleventh paragraph of the essay, Morrison says:

“What struck me in looking at some contemporary fiction was that whether the novel took place in the city or in the country, the presence or absence of that figure [the ancestor] determined the success or the happiness of the character. It was the absence of an ancestor that was frightening, that was threatening, and it caused huge destruction and disarray in the work itself… Whether the character was in Harlem or Arkansas, the point was there, this timelessness was there, this person who represented this ancestor. And it seemed to be one of those interesting aspects of the continuum in Black or African-American art, as well as some of the things I mentioned before: the deliberate effort, on the part of the artist, to get a visceral, emotional response as well as an intellectual response as he or she communicates with the audience.”

As we move through the world, I hope that our relationship to it is not defined by things outside of ourselves. Our ancestral lands and people are within us. Baby Suggs, in Beloved, taught us that “definitions belong to the definers,” and the message of this essay calls us to define ourselves as we want, on solid ground.

Other, more recent, works that have rootedness are:

1. Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi

2. Between the World and Me and The Black Panther (2016–) by Ta-Nehisi Coates

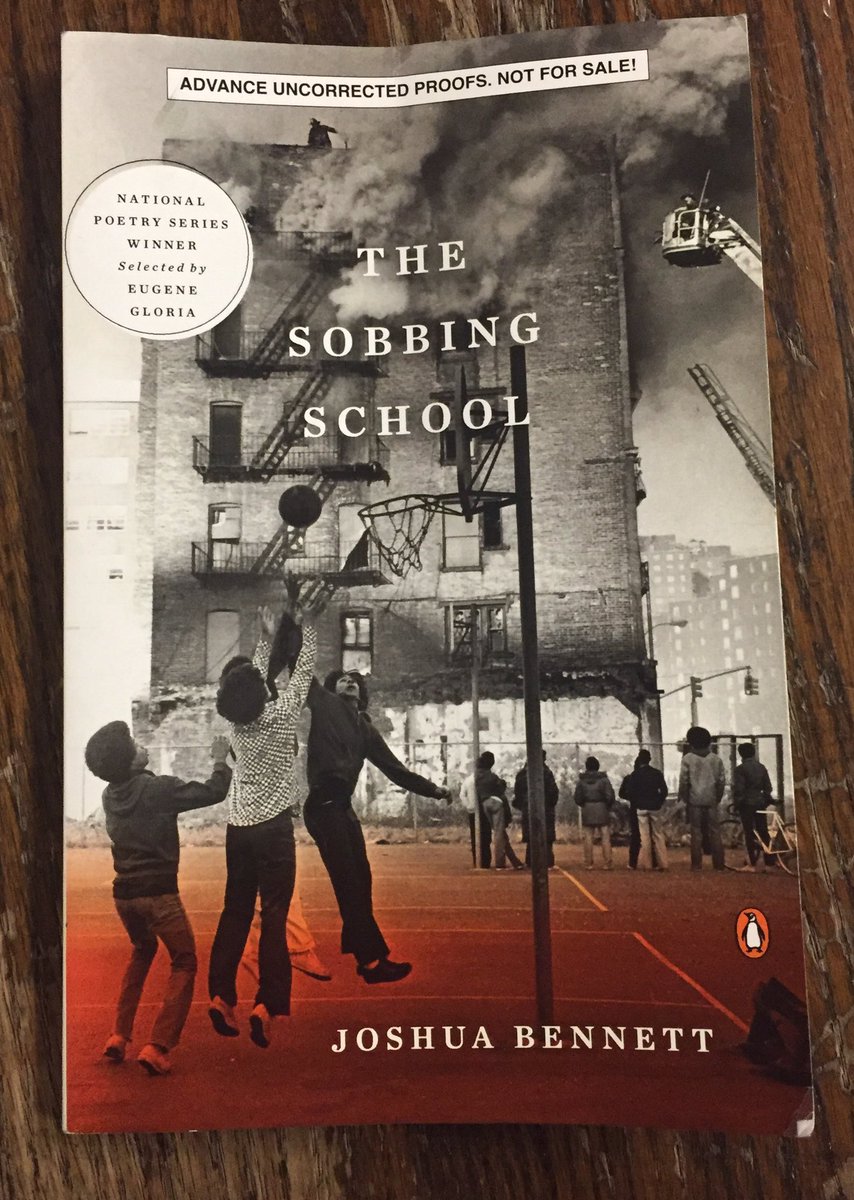

3. The Sobbing School by Joshua Bennett

4. House of Lords and Commons by Ishion Hutchinson

5. The Known World by Edward P. Jones