It’s the familiar David Vs Goliath story – one we’ve seen played out in our media on many an occasion. As the saying goes, there are two sides to every story; or is it that there are 2 sides to every story, and then there’s the truth?

It’s the familiar David Vs Goliath story – one we’ve seen played out in our media on many an occasion. As the saying goes, there are two sides to every story; or is it that there are 2 sides to every story, and then there’s the truth?

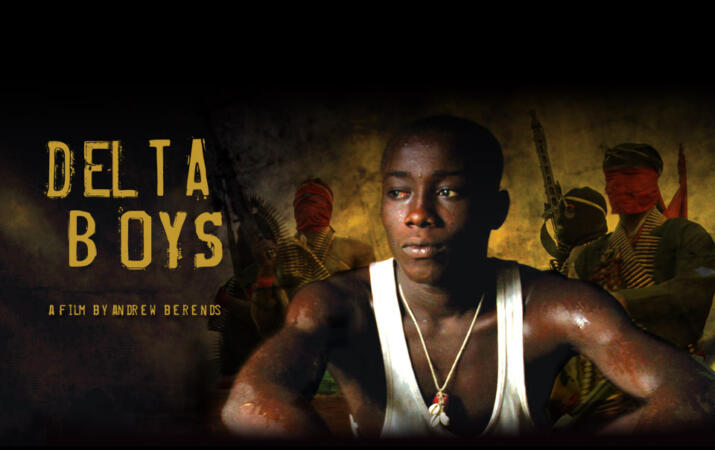

But we get mostly one side here, so it’s obvious where the filmmaker’s loyalties lie. That’s not a problem, however, since his cause is indeed one worth fighting for, if the history of the exploits by American companies in "emerging" nations is anything to go by – specifically those with valuable resources; in the case of "Delta Boys" (which received funding and support from the Sundance Institute Documentary Film Fund and the Gucci Tribeca Documentary Film Fund), we’re talking about black gold, AKA oil.

Oil companies have been pillaging land around the world of its energy resources, while, as has been reported in some cases, simultaneously dumping toxic waste in various local bodies of water, which could, and have had innumerable repercussions on the land, its food and water supply, and, in the end, the people who inhabit the land.

Of course the oil companies often refuse to accept any responsibility whatsoever, all in the name of profit. And despite attempts to challenge their occupation of these lands, none has been successful enough to shut down their operations permanently.

And so it maybe shouldn’t be any surprise when those who are directly affected take up arms against these companies, and violence ensues, as they seek to protect their resources in what is essentially a struggle for survival.

There’s no happy ending here. David doesn’t get to bring Goliath down with the stone in his sling, and cut off Goliath’s head. Despite the relentless efforts of groups like those profiled in "Delta Boys," as well as global non-violent initiatives, and films like this one, they all simply can’t match the monetary will and power of these mega-conglomerates.

Dissemination of information on a situation that many may not know about, is the idea here with films like this; humanizing the faces behind the usual "rebel violence" headlines, and making their fight accessible to even the average American, so that we all know just how connected we are in this vicious cycle of greed and oppression.

There’s no Michael Moore-esque character to entertain us, marching into the oil company’s headquarters to confront the company’s brass. There are no theatrics. The filmmaker spent many months living amongst these so-called rebels, in order to document what the mainstream news outlets rarely do, giving you a true insiders’ POV. The camera documents, and what is recorded is mostly compelling viewing.

In watching films like this, you can’t help but be conflicted, realizing that these oil companies exist because we practically demand that they do. They provide this country (and others) with a resource that, at this moment in time, is arguably essential to how we choose to live; it’s so deeply rooted in our lives that we have almost no choice but to be complicit in the damage the companies have caused, and continue to cause the world over.

I previously had the opportunity to speak to the director of the film, Andrew Berends; we talked about his motivations for making the film, challenges he faced while shooting it (like getting arrested), potential solutions, and more. Berends says he spent a total of about 14 months there – 8 months in 1 year, and 6 months the next year. He did what he could do legally, until he was given the boot.

A summary of the interview follows below:

On what drew him to the subject matter:

– I made 2 films in Iraq prior to this; it’s a globally important story that relates to everyone. We are so dependent on oil, and we want it cheaply. And the result of that is that people in places like the Niger Delta suffer as a result of it. Not only are they not benefiting from the oil that they have, but it causes conflict and suffering, and people living in extreme poverty and that is a pretty direct result of the fact that the west and the rest of the world is pretty much addicted to it, or we want it and want it as cheaply as possible, and there’s a human cost to that. I thought this was important.

On connecting the cause the young rebels are fighting to the lives of the average American:

– I think it’s very easy to see how it connects to people who consume oil. But I didn’t want to go into some prolonged speech about it. I didn’t want to keep hammering that point home. But what I set out to do was to make a film about individual people and characters, where you as an audience will care about the people in the film. For example, there’s this one younf rebel’s story that follows how he got involved, and how he’s missing his family. Because if there aren’t those human stories, then it makes it hard for audiences to be connected and be engaged. And if that happens, then that would get them interested in the bigger issue. Does that happen? Is it successful often? I’m not sure. But that was my approach. I’m more interested in following individual people stories.

On the complexities of the situation:

– There’re no heroes here. What I try to do in Delta Boys is to show that the cause they are fighting for is totally legitimate. But even if you argue that they’re corrupt, you have to go back to the socio-economic situation that they’re living in, in that many of these young men are lacking in opportunities. You have to go back to the original problem and understanding that these people are getting screwed in the first place. I think the biggest question mark is if there’s any genuine armed struggle – there are activists, non-violent movements fighting for that cause – but those really haven’t been that effective, which then makes the case for taking up arms. Maybe it starts with the right intent, fighting for social change that helps everyone; but some eventually get corrupted, and that derails what could have been a genuine movement. So few are sustained over the long-term.

On solutions:

– A good question I don’t have to answer because I really don’t know. You’d have to end greed. How do you do that? I can point fingers, but as far as finding solutions…? What I do hope is that the film makes people much more aware, and hoping that it has an effect on them, wanting to take a look at themselves, and give some thought to how they’re contributing to this situation. But in terms of how do you fix this problem… I really don’t know. People have to be nicer to each other, and less greedy. But how do you mandate that?

On getting insider access to rebel groups:

– It took a while. I went one year, and got access to one of the camps, but they changed their minds, and I quit, and went back home. But it started bothering me, so I went back a year later, and actually got access pretty quickly. Once I was there, it wasn’t hard to get access. What you have to do is share the same environs as the rebels – essentially, living in the same uncomfortable situations in terms of where and how they live, eat, etc… and eventually, the camaraderie develops and you realize that we’re all just a bunch of men underneath all this. The only real resistance is that the men wouldn’t talk without permission from their leader. They’re actually bored a lot of the time, because they spend a lot of time waiting, and they’re separated from their families. And so it’s probably entertaining for them to have some stranger/foreigner there. I could film, but I didn’t get as deep as I wanted to into their personal stories, because they wouldn’t talk unless the leader said they could share more.

On resistance from the local government & oil companies and risks:

– I got arrested, detained and kicked out of the country by the government who doesn’t want this story told. There are a handful of officials who are profiting heavily from this, while much of the rest of the country lives in poverty. The rich people are so rich – beyond what we think of rich people. But the economic divide is worse than it is here [USA]. It’s less people, but more money. A population with most living in poverty. So that was the kind of resistance I got. Interestingly, I was safe while I was with the rebels. The film is honest. It doesn’t make any false claims. I don’t think the film made such a huge stink that the oil companies would act. And it’s not the only film speaking out against oil companies. I don’t feel that the film is an extreme threat to the oil companies. But I did contact every oil company operating in the Niger Delta, and none of them wanted to talk to me. I didn’t meet any foreign journalist while I was there. Plenty of people have certainly been there. But I worked there consistently for 8 months. It was definitely risky, and I wasn’t free to work out in the open, and when I did, I got arrested and that was the end of filming. The story is being covered, but most of the pieces I saw, spent a few hours with the rebels, filmed them with their guns and boats, interviewed them, and reported the general dynamic of the fact that the region is so rich in oil and people are living in poverty; that story has been told in various news pieces, but not as in-depth as this.

"Delta Boys" is now available in North America, on VOD, as a digital download, as well as on DVD.

Watch the trailer below: