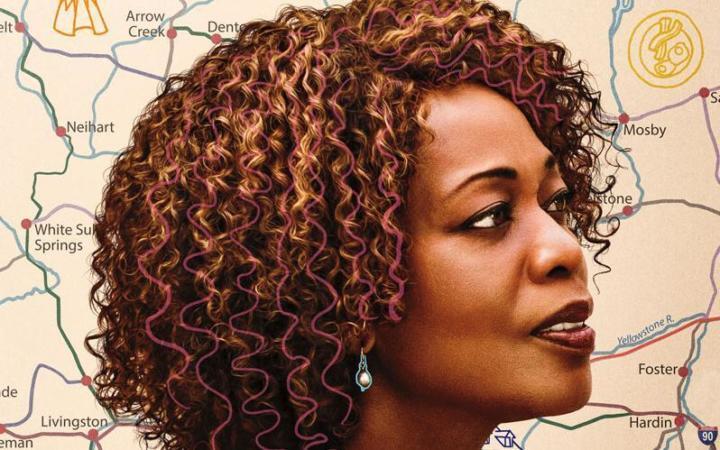

In Woodard’s newest film, Netflix’s Juanita, she plays the titular character, a Black woman, nurse and single mother of three adult children, who is ridding herself of as much emotional baggage as she’s able to, and going on a journey of self actualization. Woodard describes Juanita as, “The coming of age of a woman of a certain age story.”

The journey for both Juanita and Woodard has been a long one. It’s been about four decades since the premiere of Shange’s groundbreaking play and yet the stories of Black women are only now being normalized on the big and small screen. For Woodard, Juanita marks the first time that the veteran actress has had her name listed first on a film’s call sheet. Though her husband Roderick Spencer had written other screenplays for her over the years, they were always told that a Black woman could not be the lead in a film that would sell. Netflix disagreed.

Juanita is based on Sheila Williams’ 2002 novel Dancing on the Edge of the Roof. It was shot over twenty days mostly in Virginia. Woodard was introduced to the story over fifteen years ago when Williams handed her a copy of the book at an event. It took that long to finally bring it to screen. But Woodard was determined to get this story told because, “We hadn’t seen a story about a working class Black woman,” she said. “I liked the fact that a regular woman, who we would all know, starred in her own life.”

Juanita at heart, is a glass-half-full kinda girl. She is clear-eyed about her less than ideal circumstances, but is prone to believing things will somehow work out. However, after examining her life —one of the patients in the nursing home where she works dies, one of her grown sons is in prison, the other is heading in the same direction, and her daughter is an unemployed mother—Juanita realizes that sometimes things don’t just work out. You have to take specific steps to change them. Juanita stops asking for gratitude from her ungrateful children, stops seeking thanks from her thankless job, and decides it’s time to take charge.

Her biggest epiphany is that perhaps she has been enabling her children’s refusal to grow up. All of her sacrificing has depleted her, and hasn’t been productive for her adult children. At one point in the story Juanita says in narration, “I wasn’t doing them any good,” referring to her children. Speaking to Shadow and Act, Woodard explains that to her, this meant, “If you’re not giving yourself what you need, you can’t give [your children] what they need. Loving them does not count and what you think is love, is actually detrimental to them.”

Asked if she felt that this story might play into a stereotype of Black mothers who, though they love them, end up with a children who become statistics. Woodard replied, “I don’t think so at all. In the past was it easier to get things greenlighted that would show a mother struggling? Yes, but those [struggles] are true things that have happened.”

To the film’s credit, Juanita’s struggle as a single mom is put in its broader social context, subtly pointing out the the additional challenges that Black mothers in America face compared to their White peers. In addition to highlighting that Black women are often paid the lowest wages, the film also discusses the ways in which law enforcement play a different role and symbolize different things in white communities versus Black communities; aspects of motherhood unique to Black and brown Moms. Both the story and Woodard’s performance provide additional depth to Juanita, that refuse to allow her to be a stereotype.

“It’s [the actress’] job to bring the complexity of who that woman is even to a storyline like that,” she said.

When Juanita finally decides to live from herself, she embarks on a solo road trip from her Rust Belt hometown of Columbus, Ohio, headed for Big Sky Country. She randomly chooses the city of Butte, Montana as her destination but doesn’t quite make it there, settling instead, for Paper Moon, Montana.

Though an unlikely destination, Montana is the perfect setting for a story of someone seeking to reboot their life. One of the most sparsely populated states in the union, it literally provides abundant space for someone seeking existential rebirth. Part of the traditional American frontier, it symbolizes myriad possibilities for that new identity.

Juanita quickly gets offered a job as a cook at a restaurant run by Jess Gardiner, a chef played by Indigenous Canadian actor Adam Beach. Montana is one of the few states where the Native American population outnumbers both Hispanics and African Americans. Woodard felt it was essential that Indigenous people be prominently represented. “Real, everyday life is diverse,” she explains. “We so wanted to have Indigenous characters in the center of the frame with us.” Haunted by his past as a soldier in Desert Storm, Jess ends up becoming an important part of Juanita’s new life, not just as a boss and a friend, but as a lover. Beyond her hilarious fantasies of Blair Underwood (played by himself) romancing her, Juanita gets to have a real-life romance bloom in the wilderness, and the kitchen, with Jess–something Black moms on screen don’t often get to have.

Multiple experiences playing mothers has caused Woodard to think about the ways in which they are routinely rendered on screen. “Even in stories written by exceptional writers, even when they write a well-crafted piece,” she says, “the mother is a cliché, though it might be a good rendering of a cliché.”

She continues, “Usually people leave home around eighteen to twenty-one. When they reach back to write a mother, the writing reflects a time when they didn’t see their mother as a person. At that age, that part of your brain is shut down that would allow you to think, ‘What does my mother feel? What are her desires? Who does she love?’ So when writers reach back to write a mother, they either deify her or demonize her. Mothers in American cinema are either deified or demonized,” something Juanita successfully avoids doing. Woodard hopes that this will continue to change as more women write projects that go to screen.

“Have we seen all the different kinds of stories about Black lives and Black families? No, we haven’t seen that,” she says. “But the thing is there are more platforms now so there are more possibilities for those stories to be told as well.”

The Oscar nominee (Cross Creek) and multiple Image and Emmy award winner also hopes to inspire viewers with this story. “The everyday person watching this picture,” she says, “I want them to understand that they can change things at any moment. Mainly, I wanted this to be a gift to people to make them feel lifted and optimistic. We need joy and to believe in possibilities right now.”