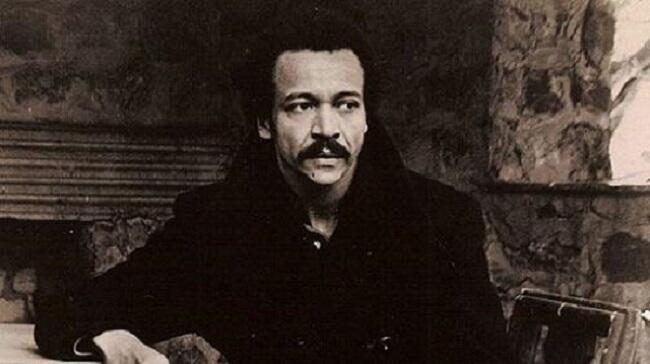

“If John O. Killens was the soldier of darkness, James Baldwin the prophet of darkness, then Bill Gunn was the prince of darkness…” – Ishmael Reed, “Airing Dirty Laundry” (1990)

I have not seen Spike Lee’s “Da Blood of Jesus” (a remake of Bill Gunn’s “Ganja & Hess”), and I doubt if I will for some time. I already wrote when I went public with development plans for my latest work, “Octavia: ‘Elegy for a Vampire” that I felt it was odd that Jim Jarmusch and Spike Lee had both released vampire films as I was just about to start one. I thought I might have gone the way of “fashion.” But of course I realized that vampire films and vampires themselves are as different to dramatists as the gangster or romance genre might be. Everyone has their own idea of vampirism and what that could mean. And that’s a good thing.

However, I write this because “Ganja & Hess” is a film so overlooked that most people are unfamiliar with it, and the ones who are, think it’s some exploitation film. These people are shocked to hear its back-story that, already, has accrued a mythic status. And I’m often perplexed as to why more filmmakers don’t reference him or acknowledge his contributions publicly. What’s even more shocking is that Lee’s “Blood” is a remake of Gunn’s masterpiece, and I find this all the more confounding. Instead of remaking a haunting delicate film into a virtuosic, ironic “art film,” why not simply acknowledge the original? Is a remake necessary? Spike Lee would have done us all a favor if he had simply written a monograph on “Ganja & Hess” and called it a day. The world needs to know more about Bill Gunn. And if artists want to pay homage to the masters, we should express what we know about life as opposed to cinema – and that would be enough…All the great masters express and teach us what they themselves know about life. And that’s what Gunn did.

Bill Gunn was a triple threat – an actor, writer, and a director. Chiz Schultz was familiar with Bill Gunn’s work (he had written Hal Ashby’s “The Landlord,” for instance) and he produced “Ganja & Hess” in 1972 for a small amount of money. Gunn wrote a “double script” which led Kelly-Jordan distributors to believe he was making a “blaxploitation” picture — but instead made his own personal film.

He was not out to “sell” blackness or capitulate to stereotypes for a buck. He wanted to make his own “cinematic poem.” One must understand the sheer guts it took to do this, to play the “spook who sat by the door” and say “yes, yes, yes” to the money men, and run off and make a serious work of art that did not care or concern itself with any of the commercial interests of the filmmaking business enterprise. That’s righteous!

When Kelly-Jordan requested an exploitive commercial re-cut, Gunn threw a chair through the window leading Kelly-Jordan to call him “crazy.” Gunn quipped, “I have more craziness in the top draw of my bureau than you will ever imagine.”

Now that took balls. If a white man had done that, they’d have branded him “passionate.” Because it was an African-American – a brilliant one at that – they had to dub him “crazy.”

Well, I always felt at home with Gunn’s fervent vision and his idiosyncratic approach to writing and directing. He is another example showing that filmmakers must be personal and unique in the way that a musician or painter is.

Directors Haile Gerima and Mario Van Peebles gave me permission to be angry and politically upfront; the absurdist Wendell B. Harris inspired me to be cerebral; but it was the “The Mighty Gunn” who affirmed my aversion to orthodoxy, who inspired my work to reflect the non-linearity, the odd rhythm, the surreal tones of life’s phases (past, present, and future), and who made me realize that a vampire film does not have to be sensational.

Like Antonin Artaud, Bill Gunn knew that horror is not in what is imagined, but in what is real. And Gunn’s vampire film is horrifying because of the layers and themes it weaves and does not resolve – colonization, cultural displacement, addiction, etc.

Bill Gunn inspired a legion of underground and avant-garde painters and dramatists to be as strange as they actually were. The freedom in that alone is revolutionary, and quite dangerous to the Powers That Be, since no system has been as aggressive in their approach to homogenize black artists as much as Hollywood.

I can immediately see how Ishmael Reed (who published Bill’s work and produced his “Personal Problems”) and Gunn may have connected as artists – as they both eschew rules and are informed by a multitude of things, bearing a collage aspect to their work. It was this that I always identified with as an artist, and, in the case of Gunn – his unabashed mixing of the impenetrable with the aggressively obvious. It was as if he blew his trumpet and muted at the same time. Those tones not only resonate within “Ganja & Hess” – a film that will leave you haunted well after having watched it (even if you don’t like it) – but are also implicated in his writing. After all, the man was a poet of the theater. I encourage everyone to read his brilliant “Rhinestone Sharecropping,” a chilling, Kafka-esque account of a black screenwriter’s experience in Hollywood and the hell that swallows him up. The actual ‘vampires’ in Bill Gunn’s book are the rich gangsters who, of course, do view themselves as racists, and are quick to drain the artist of his soul and integrity. They need soul and integrity to suck on… because they don’t have any of their own.

My vampire film shall be quite different, as it should be, but I hope it bears the uniqueness and honesty that Gunn’s brought forth. My vampire is an outcast, a marginalized “alien” caught in between her past and future, as well as America’s. My vampires are artists – some are even literal artists. But they are all sensitive – almost too sensitive. And there is no blood that can sustain them. For man’s blood is tainted; including Jesus’. And there is nothing to be addicted to – except truth. And that is what ultimately kills.

The fact that punk music as an artistic ethos plays a part in my work is no coincidence. All those who dare to be honest and to be themselves are “punk.” And Bill Gunn was creating his crowning achievements with the actual rise of punk and hip-hop; the first known black punk band Death were recording only two years after “Ganja & Hess” had been made. And Gunn died at the end of the 1980’s – when Hollywood’s Suits had already returned with a vengeance against all of the creativity set forth, even by their own “establishment” – pop star directors like Warren Beatty and Francis Ford Coppola nearly a decade before. (The Empire did, in fact, strike back didn’t it?)

In memory of Bill Gunn, I post this remarkable letter written to the NY Times in 1973 as he was defending his art and trying to teach a few lessons in the process. Of course they probably had no idea why he was so “ornery,” and they probably smirked and called him “just another bitter crazy black man.” And of course, not even the great liberal East Coast critics could admit that THE ONLY AMERICAN FILM SHOWN IN CRITICS WEEK AT CANNES IN 1973 WAS “GANJA & HESS” (Not other classics like “Mean Streets.” Not “Serpico.” But “Ganja & Hess.” Now that says something!).

I’m not shocked. Of course they labeled him “crazy.”

Somehow they don’t, and never will, understand, not only the Black consciousness of the Diaspora, but the genius inherent in a handful of living artists. Why? Very simple: the establishment prefers their artists dead.

I love you Bill.

*

Below is the text of a famous letter sent to the NY Times from Bill Gunn in 1973. Gunn also directed “Stop,” and the post-modern domestic drama “Personal Problems.”

To the Editor: (NY Times)

There are times when the white critic must sit down and listen. If he cannot listen and learn, then he must not concern himself with black creativity.

A children’s story I wrote speaks of a black male child that dreamed of a strong white golden haired prince who would come and save him from being black. He came, and as time passed and the relationship moved forward, it was discovered that indeed the black child was the prince and he had saved himself from being white. That, too, is possible.

I have always tried to imagine the producers waiting anxiously for the black reviewers’ opinions of “The Sound of Music” or “A Clockwork Orange.”

I want to say that it is a terrible thing to be a black artist in this country – for reasons too private to expose to the arrogance of white criticism.

One white critic left my film “Ganja and Hess,” after 20 minutes and reviewed the entire film. Another was to see three films in one day and review them all. This is a crime.

Three years of three different people’s lives grades in one afternoon by a complete stranger to the artist and to the culture. A.H. Weiler states in his review of “Ganja and Hess” that a doctor of anthropology killed his assistant and is infected by a blood disease and becomes immortal. But this is not so, Mr. Weiler, the assistant committed suicide. I know this film does not address you, but in that auditorium you might have heard more than you were able to over the sounds of your own voice. Another critic wondered where was the race problem. If he looks closely, he will find it in his own review.

If I were white, I would probably be called “fresh and different. If I were European, “Ganja and Hess” might be “that little film you must see.” Because I am black, do not even deserve the pride that one American feels for another when he discovers that a fellow countryman’s film has been selected as the only American film to be shown during “Critic’s Week” at the Cannes Film Festival, May 1973. Not one white critic from any of the major newspapers even mentioned it.

I am very proud of my ancestors in “Ganja and Hess.” They worked hard, with a dedication to their art and race that is obviously foreign to the critics. I want to thank them and my black sisters and brothers who have expressed only gratitude and love for my effort.

When I first came into the “theatre,” black women who were actresses were referred to as “great gals” by white directors and critics. Marlene Clark, one of the most beautiful women and actresses I have ever known, was referred to as a “brown-skinned looker” (New York Post). That kind of disrespect could not have been cultivated in 110 minutes. It must have taken a good 250 years.

Your newspapers and critics must realize that they are controlling black theater and film creativity with white criticism. Maybe if the black film craze continues, the white press might even find it necessary to employ black criticism. But if you can stop the craze in its tracks, maybe that won’t be necessary.

Bill Gunn

Author and director of “Ganja and Hess”

New York, 1973