John Singleton’s second film, Poetic Justice, was made in 1993 when South Central Los Angeles’ wounds from the injustice and uprisings of the previous year were still raw and palpable. The community, prior to, was arguably, just another urban ghetto notable only due to its proximity to Hollywood, had become, for some, synonymous with fiery hopelessness in the global consciousness.

Singleton, with Poetic Justice, pushed back at the one-dimensional image of the neighborhood. He did a brilliant job of bringing to the forefront the complexity of Black life in South Central LA that Boyz N The Hood perhaps did not. Singleton humanized Black urban working class experience by traversing back and forth, in image and dialogue, from the South Central of eleven o’clock news to the intimate, layered relationships that are the true substance of life in the so-called ‘hood. Singleton also dared to center the film around a young working-class Black woman, Justice, and have as her hero, yet another Black woman from humble beginnings, poet Maya Angelou. This was revolutionary as movies with Black women as leads are rare now and were rarer indeed in 1993.

At the center of Poetic Justice Singleton chose to put not only rapper Shakur but music royalty and megastar Janet Jackson, in her first feature film. Jackson had acted in television shows as a child and teen in the comedies Good Times and Diff’rent Strokes. Playing the character Justice, we first meet her at the drive-in, decked out in a bright yellow outfit with striking red nails and “doorknocker” earrings. She’s a carefree Black girl having a fun evening with her first love, Markell, played by hip hop artist Q-Tip. Soon, tragedy strikes and everything goes dark. Her personality loses its vibrancy. Her wardrobe follows suit. Justice is not battling grief so much as passively succumbing to it. However, one thing does remain the same; she continues to write poetry, mainly to deal with a loneliness that she herself perpetuates. When an interested Lucky walks into the hair salon where she works, she enlists the help of her MILF-y boss Jessie (Tyra Ferrell) to scare him away. Lucky, dealing with the fallout from his own failed relationship with his baby’s mother, is quick to scurry away.

At this point in history, many of us are familiar with a recurring narrative about “Blerd” (Black nerd) life. They are often ridiculed by other Blacks because they’re more interested in reading, studying, etc. than in more provincial pursuits. They are viewed as the “only” or “one of the only” Blacks in their home and/or school lives that demonstrate that type of Blackness. With Poetic Justice, Singleton presented a twist on that narrative. He seemed to be saying, “Yes, intellectuals are created in the ghetto too. The fact that they may be wearing box braids and doorknocker earrings doesn’t make them any less so either!” It was Singleton’s idea, by the way, to have Jackson wear box braids as the character Justice.

Singleton also pushed back against another myth; that Blacks, particularly working-class Blacks, don’t support each other. Justice is fully embraced by her working-class community even as they recognize that she is substantively different from most of them. This is a fact of Black life often obscured in the media. Yes, there are issues with some people being seen as different, but just as often the Black community is willing to embrace those differences and to provide the moral support needed to push a boy or girl with potential, towards success. The phrase, “You go girl!” which became a global symbol of rooting for the promising upstart, came from the ‘hood. A native of the type of community depicted in the film, Singleton decided to bring that truth to the screen. Singleton famously stated in front of a Loyola Marymount University audience that Hollywood’s decision makers, “Want Black people to be who they want them to be, as opposed to what they are.” In his work, Singleton showed Black people in their full complexity.

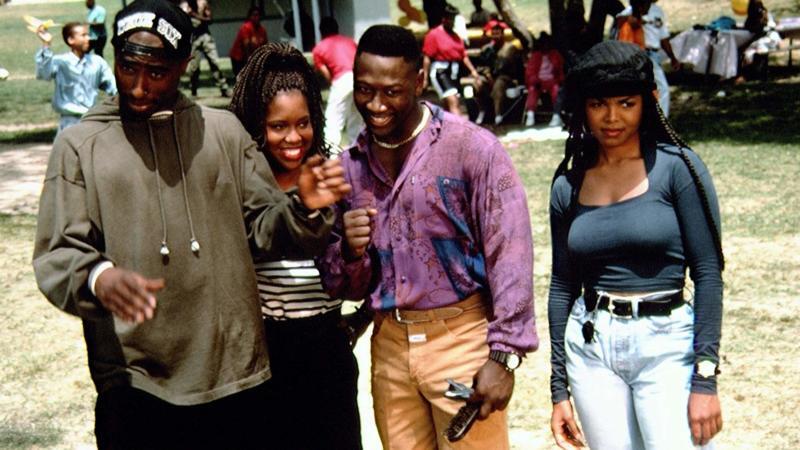

Not long into the film, it becomes the traditional “road movie,” suggested by the film’s promotional poster. Arguably one of the most iconic movie posters in Black film, it shows the two leads embracing against the backdrop of a highway, the San Andreas mountains looming above. Marrying youthful fancy with pragmatism, Justice’s best friend Iesha, played by Regina King, invites her to go on a run in the post office van to Oakland with her and her boyfriend, postal worker Chicago, and his friend Lucky.

It’s a win/win since Iesha and Justice are going to the hair show in Oakland that weekend anyway. Lucky happens to be both Chicago’s friend as well as his co-worker and will commandeer the van. He’s on his way to see his cousin Khalil, an aspiring rapper. Justice doesn’t know at this point that Lucky is the unfortunate guy she scared away at the salon but, freely indulging her survivor’s guilt, she backs off. Justice can’t betray Mikell’s (and perhaps her mother, who passed away when she was twelve) memory by having too much fun, right? As movie fate would have it though, Justice’s car breaks down and she calls Iesha and company to come to pick her up. As the postal van moves away from L.A. on the journey toward Oakland, the scene transitions from Justice’s neighborhood of modest houses with their neat little lawns into the burned out shells of buildings. It’s two worlds, but one community.

Not only does Singleton note the complexity of Black neighborhoods, but the beauty in friendships. One key example is Iesha and Justice. Regina King delivers an absolutely great performance and in fact, carries many of the scenes in Poetic Justice. Singleton renders her friendship with Justice in a manner that rings true to real life. Much as Iesha finds many aspects of Justice’s personality to be frustrating and downright weird, she loves her and values her genuineness, intelligence, and all she brings to the table. Iesha though is unafraid to call Justice on her bull when necessary and vice versa. The plot peels back layers on Iesha’s character revealing her to be a lot more troubled than her party girl veneer would have us believe. Singleton gives us Black female characters and Black female friendship drawn with a nuanced brush. He gave us Black women, not as society wants them to be, but as who they are.

For all of this, and so much more, we reflect on and appreciate what Singleton contributed to Black culture.

READ MORE:

John Singleton’s Snowfall Renewed For Season 3

11 Of Our Favorite Black Onscreen Couples

Revisit John Singleton’s Storied Career Through Photos

Photo: Columbia Pictures