There’s a lot to like in “Free in Deed,” a well-acted, unrelentingly dour experiment in atmosphere, setting and sound that will captivate you throughout. Meticulous in its attention to authenticity, the Memphis, TN-set film, assuredly-directed by Jake Mahaffy, fictionalizes the 2003 accidental death of a child during what was supposed to be a miraculous Pentecostal healing service, concentrating on a humble, predominantly African American church community where faith healings are seemingly routine.

At the center of the consternation are Abe (David Harewood) and Melva (Edwina Findley Dickerson), a deeply affecting pair – two tormented but steadfast souls striking convincingly noble chords as a burdened evangelist seeking redemption, and the distressed single mother of a child, Benny (RaJay Chandler), with a severe form of autism that makes him prone to unpredictable acts of violence. It’s a film that unfolds almost like your favorite demonic child possession horror movie, as science and religion work to rid the child of that which bewitches him (something whose origins aren’t entirely understood by the congregation) via a cocktail of drugs at first, and, eventually, after essentially being failed by a system that’s there to instead ease the trials and tribulations of families in her predicament, looks to God, via her church, and an act almost akin to an “exorcism” that results in the child’s death – the “horror” in this case being psychological. In observing 2 desperate people of circumstance and of faith, commit to dedicating their lives to the healing of a child with an “incurable” illness (wherein the “terror” lies), director Mahaffy is much more interested in the difficult contradictions between belief and actuality.

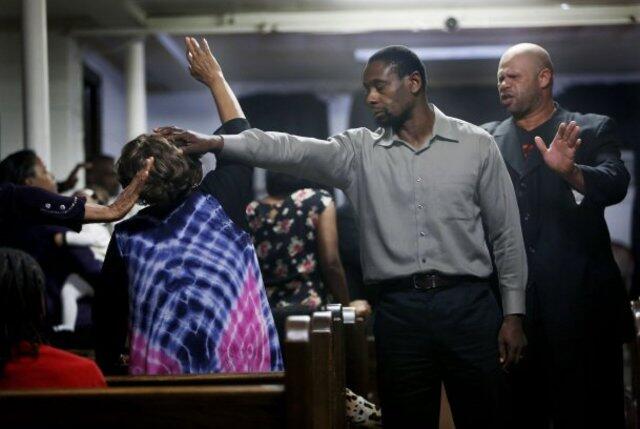

“Free in Deed” explores the gospel tradition of praying for the sick, the Christian ritual of laying on of hands as both a symbolic and formal method of healing – in effect questioning whether faith and prayer can actually heal. “How can a man crush a child to death, while believing the entire time that he is helping him?” As the filmmaker notes, this was the question that kickstarted the making of the film, 12 years ago. But the drama itself ultimately doesn’t set out to ask nor answer that question. Filmed in an observational cinéma vérité style, there is a verisimilitude to “Free in Deed” that the audience gets lost in, so much that one forgets that what you’re watching is actually a scripted fictionalized account realized by actors on a stage, delivering wonderfully subtle and effective performances; you never once doubt that they are who they tell us they are. You feel like a fly on the wall of this enclosed morass.

The audience practically becomes a member of a commune, thrust into an unnerving, claustrophobic environment, without any exposition, so much that when it all ends, you feel exhausted having being put through quite an emotional workout, relieved, but deeply affected, motivated to contemplate the world you just left behind – questions you had at the beginning, and those you might have by the end, not all entirely answered.

Lensing by DP Ava Berkofsky is sufficiently stark, clean, and even deliberately inconspicuous, so much that you’re unaware of the camera’s presence and instead consumed with the truth and crude reality it captures, with much of the drama unfolding inside a storefront church, where parishioners come for deliverance.

A laconic tribe, as if sharing an appreciation for the futility of words, even when the characters speak, it’s sometimes in hushed tones and unintelligible (except for those boisterous church scenes of praise and worship, emphasizing their importance, distinguishing between everyday life, and the security a house of God seemingly provides), relying instead on body language to communicate.

There’s barely what you’d call a soundtrack, rather a carefully designed mix of ambient sound, with audio effects added for dramatic impact, and in rare occasions, faint mood music. As the filmmaker states, “For Benny, the hyper-reality and painful, un-moderated volume of the natural world will give way to silence during the most intense episodes of sensory over-stimulation. For Abe, the evangelist, the mundanity of daily life will give way to ecstatic sounds of prophecy, revelation and impending doom of the ‘last days’.”

And smartly used sparingly, it all works seamlessly.

Ultimately, your appreciation for the film will be determined by your assessment of its credibility, and how receptive you are to its trancelike state of great rapture. As a non-believer who would typically dismiss the overt and ritualistic practices of faith healing that claim to solicit divine intervention in initiating spiritual and literal healing, I must say that it was actually quite easy for me to give myself over to the world that writer/director Mahaffy and his creative team, build, in “Free in Deed.” Instead of an expected judging of these characters and their predicaments, I empathized “freely.” The necessary care that Mr. Mahaffy, the cast and crew have taken with the material, the physical production, and the rhythm of the narrative, is palpable and valued.

The film is nominated for four 2017 Film Independent Spirit Awards: John Cassavetes Award, Best Cinematography, Best Male Lead (David Harewood), and Best Supporting Female (Edwina Findley Dickerson).

Earlier this month, SAG-AFTRA hosted a conversation with Dickerson, which was moderated by John Alan Simon. That chat was videotaped and is now available to watch in full online. First, check out the film’s trailer, and underneath it, watch the 38-minute conversation with Dickerson.