Since our journey began in this country, parents of Black and brown children have had very frank and often chilling conversations with their offspring about encounters and interactions with law enforcement. While many police officers honor their code; others wield their power by brutalizing, terrorizing, murdering and wreaking havoc throughout communities of color.

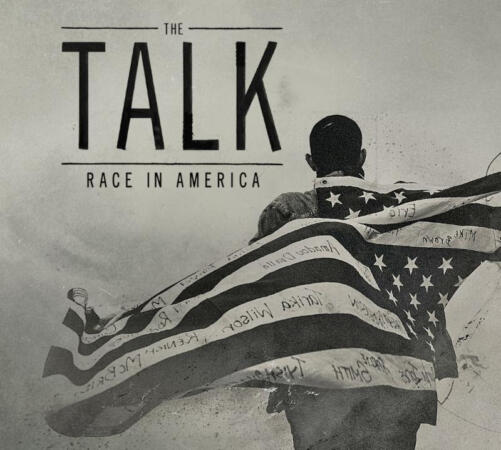

In his two-hour PBS documentary, “The Talk- Race In America” veteran filmmaker Sam Pollard tackles police and race relations across the United States of America. Through six different segments, Pollard looks at a diverse number of perspectives from various communities as well as the police themselves, showcasing what has so deeply divided us while trying to determine how we can begin to change the narrative.

Pollard also speaks with well-known figures in our society including, rapper Nas, actress Rosie Perez, and director John Singleton, each whom have had their own personal and unforgettable encounters with law enforcement. Ahead of the film’s premiere, I sat down to chat with Sam Pollard about constructing this story and what we can tell our children as we move forward.

Aramide Tinubu: Hi Sam, how are you?

Sam Pollard: Doing good Aramide, how are you?

AT: Fine, thank you. Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me about “The Talk.”

SP: My pleasure.

AT: You’ve worked on everything from “Eyes on the Prize,” to “American Masters” for Zora Neale Hurston and August Wilson, so you’re a master storyteller, especially when it comes to capturing the African American experience. So, how did you get the idea to do “The Talk?”

SP: Well, you know the idea really came from CPB, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. They felt they wanted to do something that looked at this conversation that parents of color have with their children about what happens when they interact with the police, and they wanted to look at it from all perspectives. They approached WNET about wanting to do a two-hour film and Academy Award nominee, Julie Anderson put me on this as the supervising producer. So that’s how I got involved. However, I’d like to say this, as a person of color who has been making documentaries for over thirty years, it’s been one of my main responsibilities that all of the films I do, be it “Eyes on the Prize,” or “August Wilson,” or “Rise and Fall of Jim Crow;” that we present the African American experience, because a lot of people don’t understand that’s American history also.

AT: That’s very true. For me, “The Talk” felt like a very different type of documentary for PBS. It had a very different tone, and what I really loved about it was the overarching, all-encompassing view across the country on police violence from different perspectives. We heard from the Latino community, the Black community, and you even looked at the police. So how did you tackle the different segments? How did you decide which stories you needed to tell?

SP: Well, Julie [Anderson] and I, both felt it was important to do a broad spectrum of looking at this story and looking at the complications of the story. We not only wanted to do it from the perspective of the people in the community, but we wanted to get the perspectives of law enforcement too. We felt it was important that we had stories that sort of touched on different areas. So, we had our associate producers, and our researchers do extensive amounts of research. In searching for those stories, part of this process is just getting down to a story that we think would be the most appropriate and then start making the film. And that’s where we came up with the different types of stories. We had the story of the police academy in South Carolina, that’s trying to make sure that their police officers understand how they need to be able to interact with the people in the community. That was one important story that we felt that we needed to do. We wanted to do a story about this organization called the Ethics Project that was developed by this woman named Christi Griffin. We wanted to look at how people of color felt it was important to get out and talk to white people, people who aren’t from our communities, to understand what we have to deal with every day when we become involved with the police. We wanted to do a story that looked at the Latino perspective. That’s why we found the story of Oscar Ramirez who was killed out in California. So, we were trying to make sure that we didn’t just become very narrow-minded in how we wanted to approach and be approached in telling this story.

AT: You talked about the extensive research that went into making the film. What was that process like, and how long did that take before you actually began filming?

SP: Well, we started the process in October of 2015. Then, as we did the research we started to reach out to different producers who we thought might be a good fit for the stories we wanted to do, and we brought them on in January 2016. We didn’t really start any actual production until March of 2016. So it was five months of pre-production before we actually went out into the field.

AT: What was the most difficult aspect for you in directing this film? Was there a particular segment that personally touched you?

SP: The challenge when you’re making any kind of documentary film is that you’re trying to figure out balance, and trying to look at it from all perspectives, that’s number one. The second thing that you’re always trying to figure out is how to tell a well-defined story. How do you articulate the story telling and trying to deal with these issues? We’re storytellers too; we’re not just polemicists. So, the important thing also is how do we tell the story? Do we have the characters? Do they come through as well-rounded characters who have real meat on their bones, that can engage the audience? So when you ask me about difficulty, that’s the difficult thing in making any documentary film. And the other thing that we ought to be concerned about is that we didn’t want to make films where everything is just one way; the police are terrible, or everybody in the community are victims. We try to do stories that touched on every aspect of this very complicated issue of America; racism in America.

AT: We spoke briefly about South Carolina and the police academy down there. Why did you choose that particular police department to focus on when you wanted to get the cops’ perspective?

SP: Well, you know, South Carolina in 2016 had some horrific incidents that happened. And in doing the research and looking at other police academies, we felt that this was the one that we could really dig into. And this is one where the police were open and wanted to have us. They were open to us talking to them, telling us their side of the story and trying to understand how complicated this dialogue can be between the police and communities of the color. They’re trying to make sure the police officers understand how to deal with the community. So, the fact that they gave us access, the fact that they had already had issues that they had to confront and that they were trying to deal with, made it the perfect place and perfect opportunity to tell our story. Llewellyn Smith who’s the producer of that segment, I think he did a great job in getting the police to open up and to talk, and we were able to follow some young recruits who were gonna become police officers. So we were able to follow them as well as talk to veterans from the police force there.

AT: That was very important, especially, seeing their training and learning about some of the officers who had been killed on the job. I think that really added a very deep layer to the film. It’s very textured in that way.

SP: Yeah, because It’s important to remember that the police, they’re basically the first responders in dangerous situations. And sometimes they sacrifice their lives, even though sometimes they do things that are beyond the pale. So, it was very important for us to be able to look at this from their perspective. That’s one of the reasons we interviewed, Eric Adams, who is the Borough President of Brooklyn. He is a former police officer, who could also articulate for us the complications of being a police officer and having to deal with communities of color.

AT: For me, one of the most disturbing segments was the story of Reverend Catherine Brown. I was so horrified because I’m actually from Chicago, and I don’t recall this story, but seeing that footage just really genuinely haunted me. I think Black women are often the ones who are left behind after incidents of police brutality because we are the mothers, wives, lovers and siblings. However, police violence against Black women is coming to the forefront as well, with the stories of Sandra Bland and so many other women. So, why was it important to speak with Reverend Brown about her story, and to show that footage, which is so terrifying?

SP: Well, for a couple of reasons. First of all, we knew that as we were telling the story, there wasn’t just young Black men and young Latino men who were having issues with the police, it was also women of color. We had looked at the Sandra Bland story, and at a story of a woman out in California that was six months pregnant when she was really roughed up by the police, and those stories never quite worked for us. And then, as we were doing the research, we found this story about this woman who was a lay minister who lives in Chicago. She has a couple of children, and has worked with the police and felt the police were important to her community, and then this happens to her. We thought it was the perfect story to tell because she wasn’t one of these people who said, “The police are terrible.” She thought the police were doing good things for the community. She happened to be in a situation where, all of a sudden, the police did something horrible to her, and tried to make it seem like she even tried to kill a police officer. She didn’t. And thank God there were cameras that could document what really happened out there. What really happened was the opposite of what the police had said when they tried to find her guilty of attempted murder. As you can see in that piece, not only Reverend Brown, but the people in the community were trying to figure out how to make sure that there’s communication between the community and the police. So I think it’s another piece that I’m very proud of, and Shola Lynch, the producer of that segment did an extraordinary job with it.

AT: It was eye opening, but haunting.

SP: Yeah, it’s a haunting piece, I think. When she’s calling 911 on the phone, and then you see that footage of her being dragged out of a car and being pummeled by these police officers. It’s horrific. And this is a lady who is the least threatening of any person I’ve ever met, or ever seen.

AT: Exactly. With her babies in the backseat!

SP: Yeah, it was terrible, absolutely terrible.

AT: In your opinion, how can minorities from different backgrounds come together to combat police brutality and open up the dialogue? Because, as you said in the film, the Latino community has often been concerned with immigration, so police brutality hasn’t necessarily always been at the forefront of the conversation with them. So how can we come together as different communities of color?

SP: I think the most important thing to remember, is that this should be a dialogue. Anytime any of our communities feel there’s an issue, whether it’s in the Black community, in the Latin community, if it happens to women or men, the communities should try to come together to talk about these issues. We need to try to talk about it with the police from these communities, so there’s a constant interaction. It shouldn’t be a one-sided thing where the community says, “We don’t want the police in our meetings, we want to just deal with this ourselves.” They need to open up their doors and bring the police in there, so the police can hear the issues that we might have with police departments around the country. I think dialogue is the most important thing. And I think the other thing, too, is that people have to be able to dialogue and people have to be able to raise their voice and not be silent.

AT: I agree. Speaking of this age of silencing in this Trump era, I feel like America is going to be a very different place for better or for worse when he leaves the Oval Office. So how do parents, how do people of color especially, have “the talk” in Trump’s America when we’re facing not just resistance in our communities but resistance in the government at large? What do we tell our children?

SP: You know we should tell our children that they’re Americans, that we have rights, that they have to be able to stand up and voice their opinions, and that dissent is not a horrible thing. Like anybody else, we have rights, and we have to be able to articulate those rights at any time. That’s the only way that things can change so we don’t just go into our holes and say, “The police are horrible, we don’t know what to do, the government’s horrible, we don’t know what to do.” You have to get out there and be vocal. You’ve seen it in the last month or so, with the response to this administration which is important, you have to vocally protest and oppose anything that you feel is not correct. So, that to me is an important thing. It’s something that took me a long time to understand and learn as an American, but if we don’t raise our voices, things will stay the same.

AT: So what do you hope the “The Talk” tells its audience? What are you hoping to say with your story? After all, police brutality isn’t something that’s confined to the U.S. We just saw this Black man in France being sodomized by the police.

SP: I personally want this story to challenge people to open their eyes and see what sometimes happens in America that’s not correct. And when things aren’t right, people should raise their voices. I would also hope that this film shows that there are police who are trying to do the right thing.

AT: It is a hard job. Well, thank you so much, Mr. Pollard, it was wonderful to speak with you, and I’m very excited to let our readers know about “The Talk” because it is an exceptional film.

SP: Thank you.

“The Talk- Race In America” premieres Monday, February 20th at 9PM ET.

Watch a preview below:

Aramide A Tinubu has her Master’s in Film Studies from Columbia University. She wrote her thesis on Black Girlhood and Parental Loss in Contemporary Black American Cinema. She’s a cinephile, bookworm, blogger, and NYU + Columbia University alum. You can read her blog at: www.chocolategirlinthecity.com or tweet her @midnightrami