John Ford has gone down as one of the greatest directors ever in film history. But he also was described once as a “tough, two-fisted, hard-drinking Irish sonofabitch” who was known to treat actors on his films horribly, by bullying, yelling and even mocking them. And on occasion, he was even known to actually physically attack them when he was not playing his patented sadistic practical jokes on them, or when he wasn’t on one of his regular drinking binges, which would last for days.

So why would actors put up with him? Because, in his very long career as a film director, starting in the silent era in 1917, until “Seven Women” (his final film in 1965), he made more than his fair share of classics which still stand the test of time, like “The Informer”, “The Grapes of Wrath”, “The Quiet Man”. “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance”, “How Green Was My Valley” among his some 140 films he directed in his career.

Though he made films in every genre, from dramas to historical epics, romances and even comedies, Ford has been justifiably associated with the western film and is considered one of the greatest and most influential directors in that genre, directing so many that Ford once said of himself, “My Name is John Ford. I make westerns.”

Of course being a director from what is still called “The Golden Age of Hollywood” and despite the fact that Ford considered himself a political progressive (though he was close friends with actors he worked with who were often right wing reactionaries, like John Wayne and James Stewart), his films were not above dealing in negative racial stereotypes often.

His regular portrayal of Native Americans in most of his western films – like “The Searchers”, “Stagecoach” and his cavalry trilogy, “Rio Grande” “She Wore A Yellow Ribbon” and “Fort Apache” – were as bloodthirsty savages. On top of that, in the early 1930’s, Ford also made several films with long-lambasted black character actor Stephin Fetchit, like “Judge Priest” and “Steamboat Around the Bend”, in which he played degrading and embarrassing supporting roles, often as a slow-witted, lazy buffoon.

In fact Ford started out his film career as a actor and stuntman in silent films, including D.W. Griffith’s notorious “The Birth of Nation” as one of the Klansmen who “comes to the rescue” to save the lives of white people under threat by violent “renegade” black men.

Even when Ford later directed the “passing” drama “Pinky” in 1949 for Fox, which told the story of a black woman passing for white, Fox studio head Darryl Zanuck replaced Ford with director Elia Kazan after the first week of shooting, because Zanuck, in seeing the footage that Ford shot, felt his depiction of the black characters in the film was so offensive that he couldn’t allow him to continue directing the rest of the film.

However, by the early 1960’s, when Ford was in his late 60’s and nearing the end of his long career, the director seemed to have mellowed with age, discovering and exploring a more humanist side to himself. The result was a few films in which he seemed to be, in a way, making an apology for the wrongs he committed in terms of his distorted portrayals of people of color in his previous films.

In 1964, there was his penultimate work, the nearly three-hour-long roadshow western epic “Cheyenne Autumn,” complete with an intermission, a 70MM Super Panavision print, released by Warners, which told the true story of a Cheyenne tribe who travel by foot across 1,500 miles back to their ancestral hunting grounds, while US Army troops are ordered to send them back by force if necessary.

Though the film is an ambitious attempt to deal with one aspect of how this country has historically handled Native Americans (and there are several impressive scenes in the film), “Cheyenne Autumn” is seriously undercut by Ford’s ponderous direction, a wobbly, meandering script, his stilted “wooden Indian” characters who, a lot of the time, are standing like stoic statues, with the major speaking parts played by either Latino or Italian-American actors, and too many boring side stories involving white characters.

His more modest and more successful western, also made for Warners, and released four years earlier, in 1960, “Sergeant Rutledge” is remarkable and pretty advanced for its period. It deals with a black U.S. Calvary sergeant of a regiment of black troops played by Woody Strode (who appeared in several later Ford films, including his last film “Seven Woman” playing a Chinese warlord) who is court-marshaled for raping and killing a white woman and her father as well.

Needless to say, the crime sets the townspeople aflame with hatred, and there’s a lynch mob just itching to take matters into their hands. But Rutledge faces it heroically and is not passive either, even breaking ranks and official orders to try to track down the evidence and the real killer who will clear him. But he’s eventually taken in by his own men to face trial.

And Ford, who was usually straightforward when it came to the visual aspects of his films, shows some real visual and dramatic creativity. The narrative structure is told mainly in a series of flashbacks in which information is revealed in bits, leaving us guessing as to what really happened. But Ford also effectively takes advantage of the physical, broad-shouldered, overpowering presence of Strode, shooting him often from a low angle to let him dominate the frame and the audience. And during the trial sequences, Ford frequently dims the courtroom lights, leaving only Rutledge lit, alone in the witness chair surrounded by darkness – alone and helpless as many black men on trial have felt, accused of a crime they did not commit.

Even the final scene has an unexpected dramatic impact when, after Rutledge has been cleared of the crime, barely thanks his defense lawyer and goes straight back to leading his Buffalo Soldiers out for another tour of duty. No sentimentality or hopeful message. The film makes it clear that, though a black man was found innocent, racial tensions will always exist; so what is the use of pretending that all is suddenly well? The same thing will happen again to another black man, and he probably won’t be as lucky as Rutledge was.

The one awkward movement in the film comes at the big climax when the real killer reveals himself during the trial, in a scene so overwrought and overacted that it produces more guffaws than shock. But Strode (who started his career in the early 1940’s after a legendary athletic record at UCLA as a decathlete and a football star, and who died in 1994) is perfectly cast in the lead role as Rutledge and gives a powerful performance in one of the very few lead roles he ever played, among the 90+ films he appeared in, playing mostly supporting roles, sometimes even uncredited, during the early years of his film career.

And it should be mentioned that “Rutledge” was also the first time in which a black man was seen as a cowboy, or an Army soldier, and not as a slave, a cook or a Pullman porter in a Hollywood feature western. There were of course a few black westerns made during the “race film” era of the 1940’s, such as “The Bronze Buckaroo” and “Harlem Rides the Range”, but it took until 1960 for a Hollywood studio feature western that featured black cowboys in the old west, during the mid to late 19th century to early 20 the century.

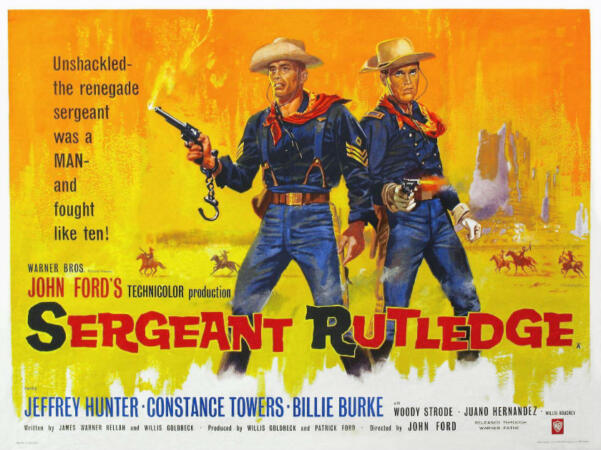

However Warners obviously thought that, though a black man was the lead in their film, the audience wouldn’t be able to handle it. And so the studio actually tried to trick audiences into thinking that the film was about the white characters. In the trailer below, Strode is given third billing, though he’s the lead. But even worse is the poster for the film (above) on which Strode appears, although his name is listed fourth and in tiny letters – even smaller that the third person billed – actress Billie Burke, who has a small supporting role with just a few lines. (What’s a brother got to do to get some respect around here?)

Not surprisingly, the film is considered one of Fords most overlooked and underrated films, and given the subject matter as well as the era in which it was made and released, it was not a box office success either. But it must have made a real impact on Ford himself, since, in the early 1970’s, he planned to come out of retirement with a new film about the life of the first black graduate of West Point, Henry Flipper. But with his ill health and advancing age, the project was dropped. Ford passed away in 1974.

As for “Sergeant Rutledge”, it was at one time, a few years ago, available on DVD on Warner Home Video; but it has been out circulation for years, although you could buy an used copy of it for $35 or more on Amazon or Ebay if you wanted it. Fortunately the DVD made-to-order Warner Archive specialty label is bringing back Rutledge at a lot lower price, starting next week.

It may not be the greatest film that Ford ever made, but it sure is one of his interesting and powerful films and definitely worth discovering.

Watch a trailer below: