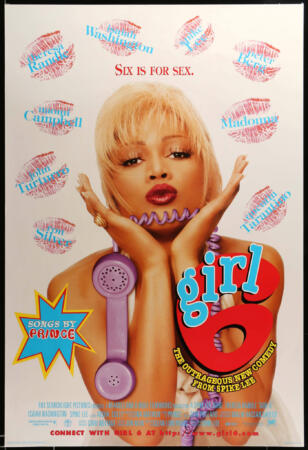

Today in film history, March 22, 1996, Spike Lee’s contentious dramedy “Girl 6” opened in theaters in the USA. At 21 years old, the movie is now officially old enough to buy liquor in these United States.

I call it one of Spike’s *forgotten* films – not because we don’t remember it, but rather because, when discussions of Spike’s film library are had, it’s one of those titles that rarely gets mentioned.

Films like “Do The Right Thing,” “Malcolm X,” “Jungle Fever,” and “She’s Gotta Have It” are usually at the top of the list. They’re also his most familiar films. Ask the average audience member what Spike Lee films they’ve seen, or know of, and one of these titles will probably be mentioned 9 out of 10 times – especially “Do The Right Thing” and “Malcolm X.”

But Spike has about 26 feature films in his oeuvre, including TV movies, and documentaries; he’s been doing this for about 30 years now, which averages to about a film a year.

But today, I’m taking a trip down memory lane with “Girl 6” on its 21st birthday.

We could say that there are 2 kinds of Spike Lee films – those that follow a much more conventional, traditional narrative path; and those that, well, don’t. Call it the “experimental” Spike Lee; Spike playing in his sandbox, with varying results.

And as I thought about “Girl 6,” I did wonder: if Spike Lee was a white director, and if this was a film about a white woman, would general reactions to it have been different, when it was initially released? I say that because I wonder if black filmmakers are “allowed” (and I’m being careful with my use of the word “allowed”) to be “different;” to push past the expected; to be experimental (there goes that word again); not just by the mainstream, but even within our own community. Have we all become so used to a certain kind of black cinema (limited to 3 or 4 different categories, especially in the last 20 years), that when something so unlike what we’ve come to expect comes along, we (everyone, not just black audiences, and of course I’m making a generalization) aren’t quite sure what to make of it. We don’t immediately understand it, and given how critical thinking in cinema isn’t exactly embraced broadly, we aren’t much interested in dissecting and closely examining those not-so easily digested films; and so we quickly dismiss them.

It’s easier to do that, I suppose, especially when there is so much else fighting for your attention.

But I think even films we consider *unworthy* aren’t exempt from that kind of critical exploration. Not that I’m implying that “Girl 6” is *unworthy* – quite the contrary actually.

And, as stated already, I imagine if Spike were a white director, and a film like “Girl 6” were about a white woman, it may have been praised for its attempts (whether intentional or not) to disrupt the expected order of things, even if it wasn’t entirely successful. Comparisons would have been made to past auteurs and styles, with critics discussing it as if it were some “neo-New Wave” construction. And its place in Spike’s oeuvre would have been a little higher on the acceptability scale, than it is currently.

Although I think we could identify both kinds of “Spike Lees” in just about all his films. I wouldn’t call him purely an experimental filmmaker (the word itself rather broad), like a John Akomfrah or Kevin Jerome Everson, for example; but I also wouldn’t call him a filmmaker in the mold of mainstream storytellers of years past.

His films aren’t always so perfectly and cleanly constructed around story, and they can have an unfinished quality about them, as if he’s still working through each one. And I actually appreciate that when it occurs, or when I make myself aware of it.

With films like “Girl 6,” I’d posit that Spike is being more than just a storyteller – pushing the boundaries of the familiar linear narrative style that most films follow; Spike Lee playing in his sandbox, with “Girl 6” being Spike at his most playful – a picuture that was sandwiched between *serious* message movies in “Clockers” (a film that he said he hoped would seal the coffin on so-called “hood” movies), and “Get on the Bus” (a celebration of the diversity in black masculinity, and black unity). His 9th feature film, “Girl 6” marked a break from his previous 8 releases, with maybe “She’s Gotta Have It” being its closest sibling (and not only because “Girl 6” borrows from Nola Darling’s opening monologue).

It was only after I watched it again recently that I considered appreciating “Girl 6,” not necessarily for the story it tells (or at least seems to want to tell – and what that is, may differ from one viewer to the next), but rather, appreciating it for the style in which it tells its story.

Although the more I thought about the film, the more layers I uncovered, and the more ways I was able to interpret it – for example, is it a story about addiction, as Girl 6 allows herself to be gradually consumed by what was effectively meant to be more of an aside, in becoming a phone sex operator in order to earn an income, so much that it takes a potentially fatal occurrence to give her the slap back into reality she needs to remember what her motivation originally was for entering that line of work in the first place, and what it was she really was pursuing.

But that’s the beauty of art, isnt it? Being able to watch a film (in this case) and receive it in more than 1 or 2 ways; each time you watch it, you see something entirely different, which can be stifling for anyone who has to write about this stuff. You want to be thorough, but also succinct.

If we summed up its plot, looking at it solely on its surface, we could say that it’s a lamentation on the plight of the struggling actress, or more specifically, of the struggling black actress – her hopes (as represented in fantasy sequences featuring star Theresa Randle playing some of her favorite screen characters), and her will to survive (becoming a phone sex operator in order to earn a living, while still seemingly working on her craft, even though it’s not exactly an ideal situation).

But what I felt was a relatively weak 3rd act, when Spike spoils all the fun we’d been having for the previous 80 or so minutes and gets a bit too serious, trying to squeeze in a lesson or two, got in the film’s way.

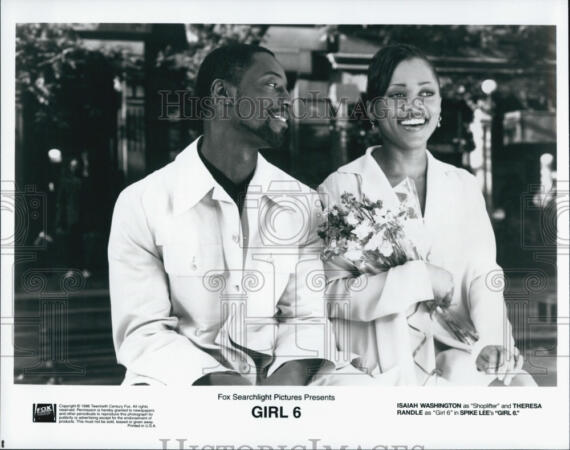

This could be regarded as a film more about mood and setting, than story. And that works for some (it works for me) and not others. Individual scenes are probably more remarkable (the ending kiss between Randle and co-star Isaiah Washington as her ex, with multi-colored telephones dropping seemingly from the sky, all in slow motion, immediately comes to mind, whether you think it has meaning or not), than when you think of the film as a whole.

It’s like the Theresa Randle show, or rather a showcase for her abilities – a highlight reel that you may have thought would lead to even more prominent roles (and she puts in a full performance, demonstrating range); but like so many other talented black actresses who came before and after her, Hollywood apparently wasn’t all that interested, even though she bared almost all, showing her breasts in the film’s opening sequence – one of those memorable, seemingly iconic, if controversial cinematic moments that not only raised eyebrows, but also may have raised her industry profile (for better or worse) the way it has for other actresses. I’m thinking of Sharon Stone’s *flash* in “Basic Instinct” for example, and the immediate impact that movie had on her career.

Not that I’m championing Randle’s *northern exposure* (let’s call it) in the opening scenes of “Girl 6;” I thought it was entirely gratuitous, and the point there could really have been made without her disrobing, not only for “QT”, but for the audience as well. It’s a misstep that comes very early on, which may have actually been a good thing in hindsight, because you get passed it very early, there isn’t another occurrence like it, and you soon forget it (well, hopefully).

I thought of that scene for a bit, trying to make sense of it, believing that there may have been more to it than meets the eye, but kept coming back to it as nothing much more than a case of a male director saying “I can do this, so I will.”

But whatever motivation or message (assuming there was an intentional one) that I was supposed to get from that moment, was clouded by the image of (and my heterosexual male appreciation for) the woman’s breasts.

Like “She’s Gotta Have It,” it’s interesting to observe Spike’s attempts to simultaneously celebrate young, independent (and all the word suggests) black women, while also seemingly wrestling with his own heterosexual male filmmaker biases and tendencies, when it comes to depictions of women.

By the way, the screenplay was written by playwright, screenwriter and novelist Suzan-Lori Parks, whose 2001 play “Topdog/Underdog” won the Pulitzer Prize in 2002. It was the first film directed by Spike for which he didn’t write the screenplay. But I wonder how (if at all) Parks’ screenplay differed from what ended up on the screen.

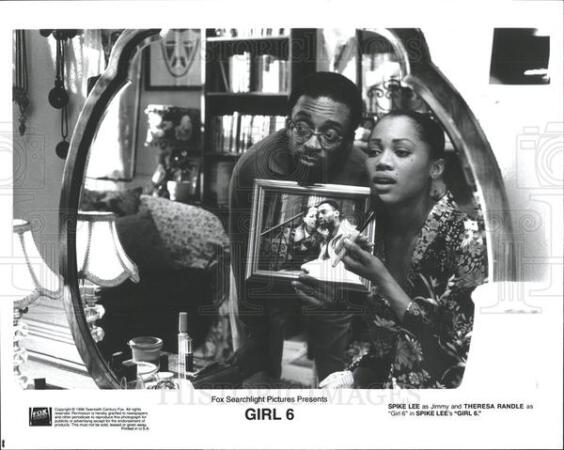

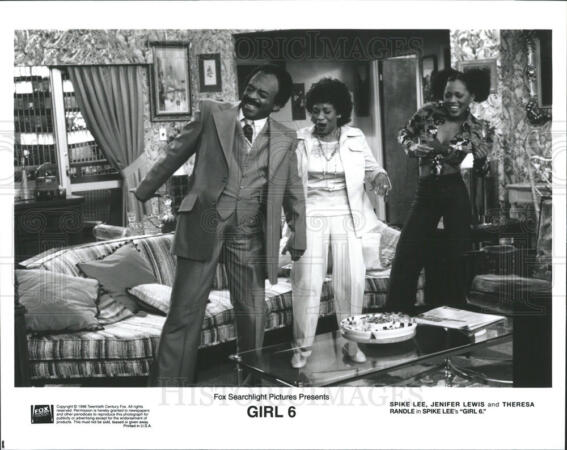

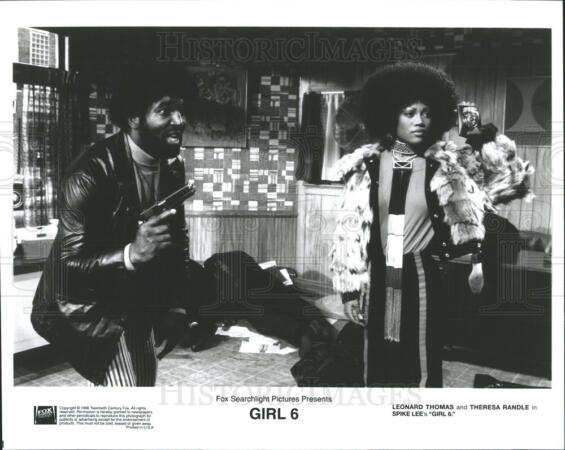

But if you’re able to get past that early moment, you’re then free to go play in the sand with Theresa and Spike for the next 100 minutes, because that’s what it often felt like (toss in several winks, via cameos from the likes of Naomi Campbell wearing a “Models Suck” T-shirt, Madonna, Richard Belzer and Michael Imperioli, and a hodgepodge of sets on which Randle wonderfully acts out her fantasies – including impersonations of past roles played by Dorothy Dandridge and Pam Grier; really, Randle shouldn’t have had to audition for another film ever again in her life!!). So your appreciation for the time you spend with Girl 6 and Jimmy, will depend on just how much you like and/or care for Girl 6 and Jimmy (Spike Lee playing a similar character he’s played in his other films, although more restrained here than usual, but still hilarious at times).

In addition to the “She’s Gotta Have It” references in “Girl 6,” I also saw thematic similarities with another *forgotten* Spike Lee film – the convoluted “She Hate Me.” Specifically, lead characters in both films find their livelihoods challenged, and are forced to make choices that they likely wouldn’t under normal circumstances, with survival being of utmost concern for each, as both become consumed with what they likely initially believed would be temporary stints in order to earn income, however out of character. And each has their moment of realization that, where they ended up wasn’t at all part of their grand plan, leading to decisions to change for the better, as we’d like to believe.

As I said earlier, this marked a departure for Spike at that moment in his career, and we could say a halfway point, when taking into consideration the 20 or so scripted feature films he’s made in total for the big screen; as we wouldn’t get to see “experimental Spike Lee” again for another 9 or 10 films when “Red Hook Summer” was released 16 years later.

Filled with familiar pieces of Spike Lee nostalgia and some of his favorite things (sports memorabilia for example), the icing on this cosmopolitan cake goes to the bold colors and warm, inviting cinematography by Malik Sayeed, as well as the wall-to-wall Prince soundtrack, comprised of both the old and the new. A separate piece entirely could be written about Prince’s contributions to the film.

Below, check out a portion from a much longer video titled “Cultural Criticism & Transformation,” from the Media Education Foundation, featuring the one and only bell hooks, waxing philosophic on Spike Lee’s career in general, but emphasizing “Girl 6” specifically. Watch her unpack Quentin Tarantino’s (QT as he’s referred to) scene in “Girl 6,” arguing that the sequence is a critique of Hollywood’s understanding that blackness and black film are ideas that can be negotiated by anyone and any filmmaker because black people aren’t *needed* to tell stories about black people, because white people can! Spike himself has said much the same thing, singling out Tarantino specifically, who may or may not have realized that Spike is actually making fun of him in the film, casting him as essentially himself.

And by the way, bell hooks’ “Reel to Real: Race, Sex and Class at the Movies” is absolutely recommended reading.

So what did you see in “Girl 6”?

Watch a 15-minute cut of the film below; and underneath, watch bell hooks’ assessment of the film and more: