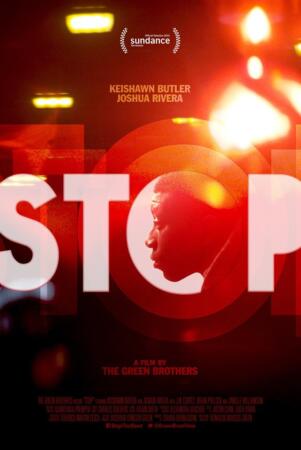

Reinaldo Marcus Green, a native New Yorker developing a real name for himself in the world of independent filmmaking, is a voice to listen to. His short film, “Stop”, premiered in the U.S. Narrative Shorts program of the Sundance Film Festival. A riveting, tension-filled work that studies the uncomfortable details apparent in racial profiling,

“Stop” takes place over the course of one night, as Xavier (Keishawn Butler) an African-American teenager living in Brooklyn, makes his way home after an afternoon of baseball practice. Over the course of his trip, he finds himself victim to stop-and-frisk courtesy of two NYPD police officers. Subtle and unassuming, the film captures the feeling of, if not paranoia, then a consistent worriedness, a shaken up feeling that remains in the back of your mind.

I previously spoke with Green about the film and his thoughts on police brutality and stop-and-frisk. Read a summary of that conversation and check out the short film “Stop” in its entirely below.

ERIK LUERS: When did you shoot Stop? Given its timeliness, I’m sure some may feel it’s a response to the recent injustices that have been taking place involving police brutality.

REINALDO MARCUS GREEN: [The film was a part of my third year class at Tisch at NYU]. Todd Solondz was my teacher. We workshopped the script from January through May (it was the spring semester) and we spent several weeks figuring out what kind of story I wanted to tell, making several revisions along the way. The actual shooting process took place over two short nights, with four hours one night and three hours the next, all on location in Red Hook, Brooklyn. What’s occurring in the media now hadn’t happened yet. Of course, there were a number of events, portrayed in Ryan Coogler’s “Fruitvale” for example, that were in the news beforehand, but it really came together after the highly controversial Trayvon Martin decision, after George Zimmerman got off. That’s what really sparked the idea in me. I thought, “what if I was Trayvon Martin on my way home?” That was the impetus for the script. When I came back to school that semester, I knew I wanted to do something featuring that, but I didn’t know what my take would be. And then it came to me: what if I was walking home and someone stopped me? What would that feel like? The initial idea was for the film to feature a particular thought process behind what was happening, that it would be portrayed in a voiceover. I eventually didn’t go with that, instead choosing to create a beginning, middle, and end, showing the result [of the evening].

EL: The film takes place over a few hours. Was it important that the entire event (its prelude, the actual event, and its aftermath) be presented over one evening?

RMG: In terms of creating a short film, it just made sense for this particular piece. We get to see what Xavier was doing right before the event — he’s playing baseball — but he could have been doing anything. I was an athlete growing up, so it made sense that he’d be a baseball player. I also wanted to show what he was thinking during and after the confrontation with the police, to see how he makes a decision based off what’s happened to him.

EL: In the opening dialogue sequence, you realize Xavier has a bright future ahead of him in a matter of seconds. He could be great at baseball. He and his friend talk about women and applying to college, etc. How clear did their positive outlook have to be? How quickly could you get that across?

RMG: I wanted to make sure that was clear, that he had an opportunity that could’ve been taken away from him. He could have lost something very big after this incident. It was very important in those first few scenes that the viewer understand that he’s aspiring for something larger, to uplift his community. It was super important in that first scene that his aspirations came across. We later see him on the bus, tossing a baseball up in the air, thinking about the game. It’s something that’s really subtle, adding another layer to the importance of what he has going on in his mind. He’s not thinking about getting stopped. He’s thinking about the game.

EL: On his walk home, there’s one shot from the police officers’ point of view, in the cop car as they cruise the streets looking for someone to interrogate. The film is filled, I think, with subjective camera choices…

RMG: It’s funny because we had more material with the police, and yet I wanted to stay more within Xavier’s head. I only cut to that shot for a second. It was much more for suspense purposes, as we don’t know who they are (we don’t know that they’re police at this point) and it could very well have been a gang following from behind. I wanted to build that suspense, as there’s as much taking place in your mind as there is on screen. By cutting to that shot, it adds suspense to the question “who’s watching him?” We don’t know, and our heart skips as we’re watching.

EL: When the police officers confront Xavier, they assume he had just come from playing basketball — which screams of ignorance — and keep asking him to speak up. These seem like pretty common intimidation and fear tactics to use on someone. How carefully did you work on the dialogue for the police officers?

RMG: The actors playing the cops are actually cops in real life, and so they had a very naturalistic way of dealing with the situation. Stop-and-frisk is something they both had experience with. It’s something all cops are familiar with, and it’s not necessarily viewed as a bad thing within the department. And even though the two men are cops, they’re also actors. One of them is now starring on a hit show “Gotham,” although that happened after our shoot. Both men were really open to this idea for the film, and as cops, they realized how important the issue was to address on both sides. There was a little bit of resistance in terms of what they could say, so we needed to really stay with the script and not make them too over-the-top in regard to their dialogue. I knew I didn’t want the film to feature a fight or a scene of our lead character getting shot. It wasn’t about that for me.

EL: Does it add anything by making them plainclothes cops driving in an unmarked car?

RMG: I think so, yes. For the person who’s being stopped, they don’t necessarily know that they’re being stopped by cops. They may have a flashlight or something like that, but they look just like you, so I would be inclined to run or be frozen and be scared. I don’t know who’s approaching me. Even though they’re cops, they may not always appear that way. There’s always the fear of “well, they look like me, so am I sure they’re a cop? Are they pretending to be a cop in an attempt to rob me?” There are all these elements that go in to not seeing the blue and white and hearing the sirens.

EL: The whole film, from the darkened streets lit by the city’s ambient light, to the lights on the cop car and the claustrophobic apartment that Xavier calls home, seems naturally lit.

RMG: All the testaments should go to Federico Martin Cesca, my Director of Photography. We did in fact shoot with all natural light. We scouted two days before we started shooting, knowing that we really didn’t have a lot of money. We had to use practical locations, mostly exteriors, and wound up shooting in our lead actor, Keishawn Butler’s house. That was his apartment and that was his mother in the film. We used the elements that were already there to our benefit. His house is pretty well-decorated, so we altered that by keeping the lights off, and I think it works for the film.

EL: The final sequence in the film is portrayed in a single shot, from Xavier’s elevator ride up to his apartment to the final moments in the bathroom. This continues an interesting choice of often keeping the camera behind Xavier and having it follow him throughout the evening.

RMG: In my last film, there was a very long take that, by not cutting, allowed us to stay within the character’s head. I thought that by staying within that one shot, we’re allowed to think as he thinks, in real time. He’s making a decision as we make it with him. The apartment location we had in “Stop” lent itself to that filmmaking choice. We could be with him and see what he’s thinking. We don’t know if he’s going to go home and slit his wrists. There were several things that were going through my head about what someone would do in that situation. By keeping the camera with him, I thought it was very interesting. He knew all along, from that very moment, that this was a very close situation and one that could occur again. Even if he doesn’t want to find himself in the situation again, if it does happen, he’ll be much better prepared. By playing it out in real time, we never wanted to let the audience breathe.

EL: Could you talk a little bit about the brief exchange that Xavier has with his mother? She asks him how his day was, and he remains casual and doesn’t inform her of the incident. It’s shocking and painful that it almost feels like a matter of fact, that this frightening event won’t ever be discussed between them.

RMG: That scene wasn’t quite written. It was supposed to involve a father, but Keishawn Butler’s mother was at the apartment at the time and was willing to be our actress. We chatted for a few minutes before shooting the scene, and I asked her about the kinds of conversations she has with her son. She said that sometimes he comes home and goes straight to his room and they don’t really talk. She’ll say “how was your day?” and then he’ll go into his room and use his phone. I thought that was something we could play with. He’s this way in real life, so I thought we could try to keep the situation as real as possible and see how it plays in the overall shot itself. This is a typical interaction between Keishawn and his mom, a teenage boy who has other things going on and isn’t really interested in sharing his secrets with his mother. I thought that was something very real and it played into the overall narrative of the film.

EL: While there have been reports that stop-and-frisk numbers have gone down in New York City, there have, of course, been some very high profile stories involving police brutality recently. What are your thoughts on stop-and-frisk? Is it targeted to specific groups of people? It’s received a lot of attention and rightfully so.

RMG: I think it’s no secret that people of color have been the target of stop-and frisk policies in New York City. If you look at the amount of young black and Latino teenagers being stopped compared to other races, the numbers are alarming and astronomically different. That needed to be addressed, as it affects the entire country. It happens everywhere. While they may ultimately end the policy of stop-and-frisk, they could continue it by calling it something else. The issue is the profiling aspect, stopping people because of how they look. I wanted to approach it in a non-didactic way, that allows people to think for themselves. The choice is up to you about whether you think stop-and-frisk is right or wrong. I’m presenting it in a very matter-of-fact way. I think the issue needs to be addressed, and that’s why I made a film about it. I hope the film brings attention to this issue in a positive way, that asks if there’s a more positive way to go about stopping people. If we have to do our jobs, maybe there’s a better way to do it. On the flip side, are we doing everything to make sure that we’re preventing this from happening in the future? We have to be ready for it, even if we know it’s not right.

Watch “Stop” in full below: