Time is precious. But it can also be haunting, especially when an outside force is holding the years, minutes and moments we use to clock our lives in the balance. For people who are incarcerated, the United States prison system is adamant about making sure time is something it owns.

For over 20 years, Sibil Fox Richardson, aka Rich Fox, a businesswoman, and an advocate, has been doing all the groundwork to push for the release of her husband, Robert Richardson. On September 26, 1997, in an act of desperation, Rich and Robert robbed a credit union. Though Rich was able to get a plea deal, serving out three and a half years for her role in the crime, Robert was sentenced to 60-years in the Louisiana State Penitentiary, one of the worst prisons in the United States. Time is their story.

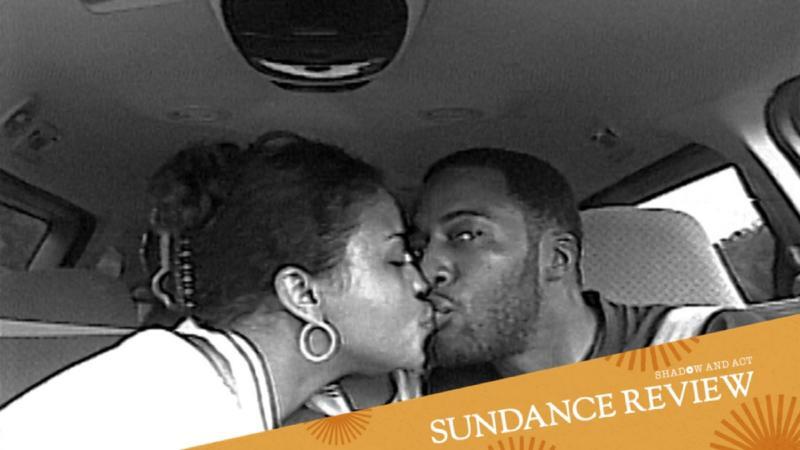

Told in black and white with director Garrett Bradley’s modern-day footage interwoven with Rich’s personal home videos of her and their sons, Time unveils a life of waiting and longing. From her own words, prior to and following her release from prison, the audience learns more about Rich. She welcomes us into the life she’s carved out for herself. We watch their six boys transform from pamper-wearing babies into towering bearded men. Rich has found joyous moments in the past 20 years. Yet, the fight for her husband’s release is the singular goal of her life.

Regal and fearsome, Rich more than takes responsibility for her part in the robbery. What she doesn’t accept is the time that has been stolen away from her family. She’s constantly irritated by the lackadaisical attitudes of judges and judicial secretaries who can’t seem to make the correlation between their day-to-day work and the lives that dangle in the balance.

As Time swivels between the past and the present, we sit with a self-assured Rich, who never cowers in the face of her past mistakes or what she perceives to be right. It’s an interesting contrast to her mother, who suggests on more than one occasion that Rich should humble herself to make headway with Robert’s case.

Though she loses her cool once in the film, Rich’s anger at the racist and unjust prison system that has sliced her family in half is a constant through-line. The years have slipped away, yet the pain of watching her boys grow up without a father in their home continues to fester. Though she has done everything in her power to raise five Black men and one vivacious little boy, allowing them to experience fatherhood is something she’s never been able to give them. The memories she holds close to her heart, and the longing for what could have been, prevent Rich from moving on. Still, just as quickly as she lashes out following yet another fruitless phone call, she composes herself. Her tears are dried and her warm southern accent returns to its level tone. Once again, Rich is ready to press forward in the war for her husband’s life.

Time sits at a zippy 81 minutes, but Bradley often forces the audience to stand still with Rich. We wait with her on hold with yet anther judicial secretary, at the gym, at church and on the phone, her youngest son, Robert Jr., just near enough to hear his father’s voice from the speaker. For two decades, Rich’s life has been a waiting game and Bradley makes certain that the audience understands this.

While most films on mass incarceration and prison reform place their audiences in jails and courtrooms, Time does something different. Through personal conversations, we learn about the two monthly visits, two hours each, when Rich is allowed to visit Robert. Viewers are made aware that even in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, Louisiana refused to cut the prison budget and release those with ample time served. We understand the dream that Rich and Robert had for their family and how Rich’s sheer will is also in their boys. At times, the sons are more willing than their mother to openly discuss the pain of their father’s incarceration. One lesson they have learned from Robert’s absence is how to advocate for themselves in both their educational and professional lives.

Time is about moments, lives lived, faith, pain, tenacity and sheer love. This isn’t a film about policies and legal jargon. It is a story about human beings, and an entire family hanging in the balance, held captive by a system that refuses to see them.

Time premiered at the Sundance Film Festival on January 25, 2020.

READ MORE:

‘The 40-Year-Old Version’ Is An Ode To Black Womanhood And Putting Yourself On

‘Bad Hair’ Has A Lot To Say But Never Says It [REVIEW]

‘Charm City Kings’: Coming-Of-Age Drama On Black Dirt Bike Riders Gets Release Date

Sundance 2020 Includes ‘Zola,’ ‘Charm City Kings,’ ‘Sylvie’s Love’ And More

Photo: Courtesy of Sundance Film Festival

Aramide A. Tinubu is a film critic, consultant and entertainment editor. As a journalist, her work has been published in EBONY, JET, ESSENCE, Bustle, The Daily Mail, IndieWire and Blavity. She wrote her master’s thesis on Black Girlhood and Parental Loss in Contemporary Black American Cinema. She’s a cinephile, bookworm, blogger and NYU + Columbia University alum. You can find her reviews on Rotten Tomatoes or A Word With Aramide or tweet her @wordwitharamide